Whether you consider tourbillons to be the ultimate in haute horlogerie, or – like me – you think they belong in pocket watches, Breguet’s anti-gravity device remains the yardstick by which watch houses are judged. It should therefore be no surprise that TAG-Heuer, a brand feverishly pursuing credibility not just as a manufacture, but one able to produce movements to challenge the very best, has chosen to fit a tourbillon to its latest assault on the state-of-the-art.

Called the MikrotourbillonS, it is not the first chronograph to be fitted with a tourbillon; the magnificent Jules Audemars Tourbillon Chronograph, Breguet’s Marine Tourbillon II, and Zenith’s Academy spring to mind, as do a bevy of grand complications. But TAG-Heuer hasn’t fitted a tourbillon merely to join a no-longer-exclusive club: there is actually a rational purpose, especially in light of their recent run of ever-more-precise chronographs.

With a price tag of £175,000 in the UK, or $275,000 give or take a few bucks, the MikrotourbillonS follows the belt-driven Monaco V4, Mikrogirder, Mikrograph, and Mikrotimer Flying 1000 as TAG-Heuer’s way of showing the Swatch Group that it will survive their plans to reduce the supply of movements. Moreover, such outré timepieces demonstrate that TAG-Heuer has the ability to innovate and to produce complications in-house, with the ease and facility one associates with sniffier, more elite auteur houses.

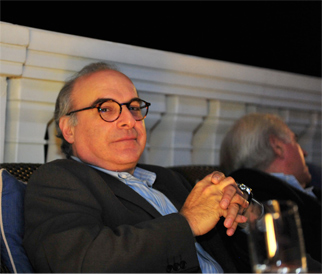

Guy Sémon, Vice President of Sciences and Engineering, explained one other crucial motive for creating the MikrotourbillonS. TAG-Heuer is working with COSC to devise a new chronometer certification for chronographs. According to Sémon, COSC’s current certification deals only with the watch itself, not the chronograph. The company believe that any chronograph submitted for whatever new certification might emerge will improve its odds for success if it is a fully integrated design, rather than a watch-plus-module. Sémon admits that the MikrotourbillonS has been created to “set the stage for the first-ever dual-certifiable chronograph.”

They’re not taking any chances. The double-train, double-barreled MikrotourbillonS is said to be both “the world’s fastest tourbillon,” as well as “the first ever tourbillon on a 1/100th of a second chronograph that can be started and stopped.” To achieve this, the MikrotourbillonS has two complete tourbillon mechanisms, one for the watch itself, and one for the chronograph segment. The first beats at 4Hz (28,800 beats per hour), with standard tourbillon rotational speed of once a minute. The second – “the world’s fastest tourbillon” – serves the 1/100th-of-a-second chronograph and is dynamically compensated to run at 50Hz, so it operates at 360,000 beats per hour and rotates at 12 times a minute. Furthermore, the tourbillon has no cage “and can be started and stopped thanks to the ‘dual chain’ architecture.”

One of the challenges that has always faced chronograph designers is preventing the chronograph’s operation from disrupting watch operation. The Mikrograph of 2011 contained two independent “kinematic chains” (I think that’s TAGspeak for “trains”), one for the watch and one for the chronograph, but integrated into the same movement. This also applies to the MikrotourbillonS.

An immediate benefit is the elimination of a clutch, while separating the watch from the chronograph eliminates the risks of either effecting the other in any negative manner. Energy loss is also reduced. This topology ensured all “Mikro” timepieces are ISO 3159-compliant; the Mikrotimer and the Mikrograph are COSC-certified with the chronograph function running, which TAG Heuer says is “a feat virtually impossible to achieve by conventional mono-frequency chronographs.”

As for the MikrotourbillonS, its automatic movement contains 439 components and measures 35.8×9.7mm. It contains 75 jewels, the aforementioned twin barrels and two tourbillons, providing power reserves of 45 hours for the watch and 60 minutes for the chronograph. The 45mm diameter case ensures water-resistance to 100m, though only a profligate madman would want to dive with a watch this costly.

Half of the anthracite dial has been excised to reveal the two tourbillons, still leaving enough surface area to display hours, minutes, a central hand for the 1/100th-of-a-second chronograph with its counter running around the circumference of the dial, chronograph minutes at 3 o’clock, chronograph seconds, and 1/10th-of-a-second at 6 o’clock. The power reserve is located at 12 o’clock.

As befits a watch of this level, the company has ensured that it is as luxurious as it is innovative. Rose gold, tantalum, and rubber provide subtle color contrasts, enhanced by white accents. The striped dial recalls other TAG-Heuers, but the tourbillons still seem a non sequitur: this is, after all, TAG-Heuer, not Christophe Claret.

At the launch, Sémon was questioned about the suitability of TAG-Heuer issuing a tourbillon, something it has resisted for years, for Rolex-like reasons: it’s a horological mind game, rather than a worthwhile development like silicon, or the co-axial movement. But, as so many champions of the tourbillon can demonstrate, the device can most certainly improve accuracy if done properly – as Greubel Forsey demonstrated by winning the 2011 International Chronometry Competition. As Sémon explains, TAG-Heuer wanted want to make the most accurate mechanical chronograph ever produced, period. If it took a couple of tourbillons to do it, then they’ll reap the whirlwind.

(Ablogtoread, 2012)