One day, a book will be written about the brave brands that kept the faith during the years between the arrival of quartz and the revival of mechanical watches. If you weren’t a watch enthusiast 15 or 20 years ago, you’d be unaware of the gloom that beset the industry in the wake of quartz, especially given the industry’s current hyper-activity.

Equally, you’d be unaware of the courage possessed by watchmakers who became company founders during this period, making mechanical timepieces in the face of a battery-driven onslaught. People such as Gerd R. Lang, who launched Chronoswiss as a means of preserving the tradition for the mechanical chronographs he loves, or Dr. Luigi Macaluso, who revived Girard-Perregaux, deserve our thanks. Among them should not be forgotten an elegant Genevoise antique jewellery expert named Dominique-Marie Pibouleau.

In 1987, Pibouleau decided to add a line of watches to her already-successful jewellery business; her partner was Franco Giolla, a highly-regarded jewellery designer. The two of them created a range of affordable watches that predated nearly every other watch brand’s appreciation for the qualities that dominate the watch market to this day: tasteful, intelligent exploitation of ‘retro’ touches, larger-than-average cases, huge numerals and the use of atypical colours – for dials and straps – to add elements of both glamour and fun.

Think about it: fully six years before Panerai was relaunched in Florence, Pibouleau’s brand MHR – also called ‘Mahara’ – offered watches with dials based on those found in pre-Word War II aircraft. Yes: the now-obligatory, over-sized 3-6-9-12 numerals seen in just about every brand’s mock-military model since Paneral re-appeared was first revived on the now-forgotten MHR watches.

[Note: Rolex has always had the Explorer 1 in its catalogue.]

Because MHR was all-new and not the reincarnation of some forgotten marque, it never purported to be what it was not. This made MHR far more honest in every way than some of the names that have been resuscitated as if the intervening 200 years never happened.

If any lack of ‘pre-history’ might suggest that the brand was designed for fashion rather than any concern for horology, think again. With the exception of one or two men’s and ladies’ models fitted with Swiss quartz movements, all of the watches used ETA or Piguet automatic, mechanical movements. What made the MHRs stand out from the other remaining, affordable mechanical watches of the day were the cases: solid, robust, and looking and feeling like they’d withstand any punishment you could inflict.

They were in instant hit, with the company selling 5000 watches in the first year. Of course, the Japanese and the Italians took to them first, and it wasn’t long before MHR realised that, by virtue of keen pricing, their customers kept coming back for more. Enter the next clever innovation: fun with colours.

Common to all of the watches were anti-reflective mineral glass, and a screw-down crown providing water resistance to 30 meters. Measured at the dial, the watches ranged from 27mm to 37mm, and were available with stainless steel bracelets or straps in leather, denim or linen, with either deployment buckles or folding clasps.

The diving watches were water-resistant to 300m and had a one-way rotating bezel to check decompression time, and rubber straps or steel bracelets. Also available during the brand’s lifetime were square-cased watches, gold or two-tone models, GMTs and chronographs, but the defining model was an hours-minutes-seconds classic called the Sparviero S.79.

Fitted with an ETA 2824-2 calibre, the Sparviero boasted a salmon-pink dial and black numerals, and a leather strap with suede lining; an Irish linen strap was also supplied for warm weather usage. The hour hand featured the same ‘Mercedes’ feature as seen on certain Rolexes, while the sweep seconds-hand bore a large round disc a few millimetres from the end to add to the legibility.

With an overall diameter of 39.3mm, it was considered large for its era. And with a pre-Euro price of 1,330,000 lire/SF1,530 (call it circa £650) it was a giveaway. MHR coolness even extended to the packaging: cardboard boxes that looked like miniature filing cabinets.

I fell in love with the Sparviero the moment I laid eyes on it, but ended up missing the initial run and purchased a near-identical model with date beneath a ‘cyclops’ window at the 3 o’clock position, and with the same pink dial. I also had the foresight to purchase the smaller model, with black dial, and a Bugatti watch I purchased from the pre-VW-owned incarnation of the marque turned out to be made for them by MHR.

Subsequent visits to Milan over the years revealed that MHR was doing for collector-types in its sector of the market what Swatch had done at a far lower price point. The same watch was offered in various colours, changing seasonally, with the Sparviero joined by the Red Devil (red dial and strap), Bleu Leman (navy blue dial and blue denim strap), Black Storm, Papier Mais, Sparviero Rose, Green Pepper (dark green dial with yellow numerals), and other variants including one with a matte black dial with gloss black numerals, and a ‘reversed out’ Sparvieros with grey dial and pink numerals.

On 6 November, 2000, Swiss Watch News published the announcement of a ‘Double Acquisition For Franck Muller,’ and how the company had ‘plans to develop its brand portfolio.’ The group acquired, at the end of August, the assets ‘of the Genevan manufacturer Mahara Montres (MHR),’ including the retail outlet in Geneva. ‘These “middle range” watches will benefit from new design.’

Or so the brands’ fans had hoped. From that point on, there was silence. Muller did, indeed, develop new brands, including Pierre Kunz and the absurdly-named, noxiously-styled European Company Watch, but nothing was heard again about MHR. Shortly after, the web-site closed. I knew it was all over when the canniest watch retailer I know told me that he had hidden away a tray full of MHRs as a future investment.

Alas, it’s probably now too late to revive the brand, especially if 3-6-9-12 is truly MHR’s primary calling card. Why? Because 3-6-9-12s are everywhere. Panerai has re-established itself as one of the most coveted makes on the market, Bell & Ross have done an amazing job providing the market with an enture selection of 3-6-9-12s, albeit at the next price point above MHR’s original market placement, while individual versions of regular models, such as JeanRichard’s military-dial Bressels, Eberhard’s Traversetolo, the Omega Railway and countless others have followed the same ‘big number’ path.

As for colours, Chronoswiss recently launched its Timemaster – if ever there was a watch that screamed ‘functionality’, this is it – in fetching shades of yellow, blue, green and other hues, while Franck Muller has always had a salmon dial or two in its range. You can’t escape orange dials this year. Or coloured linen straps.

For all of the pieces sold, MHR has all but vanished – not even eBay produces more than the occasional MHR for sale. So it looks like the collectors are hanging on to them. The next time anyone tells you there’s anything new under the sun, spare a thought for MHR, who pioneered today’s cool details nearly two decades ago. But remember, too, the famous aphorism about pioneers: they’re also the ones who got shot in the backside with the Indians’ arrows.

© Ken Kessler, 2005

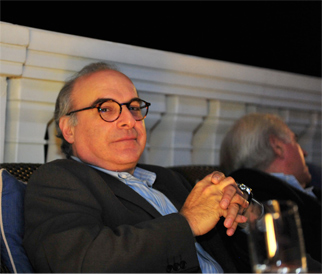

Photo by the author of his own watch