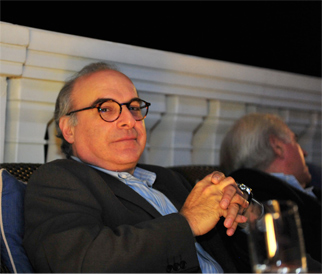

(Max Busser, centre, with Marcus Margulies and Wolfgang Sickenberger)

There exists a handful of companies who use outside watchmakers to create new models. The thinking is clever: by looking to others, a brand ensures it will never be stale or predictable. It began with Harry Winston’s Opus 14 years ago, more recently by Maîtres du Temps, and is the raison d’être of MB&F, short for “Maximilian Büsser & Friends.”

MB&F’s natural affinity for this method of watch creation is understandable: Büsser was a key element, after he moved from Jaeger-LeCoultre to Harry Winston in 1998, in the conception of the Opus Series, for which each model – one per year – is conceived by a different designer. Thus he has, as the British would say, “previous” in employing outside masters to help with his fabulous creations. But even if Büsser did not temper his own imagination with the input of others, his personal approach is radical, inventive and adventurous – and not only to watchmaking.

MB&F is not, however, out to reinvent complications nor techniques that were perfected centuries ago. Instead, Büsser is content to present the display of time in novel ways, to take a fresh approach to how mechanisms are housed. If anything, Max is also a traditionalist at heart, which explains the existence within the otherwise outré MB&F catalogue of the Legacy Machines. This is a line which pays homage to the greatest watchmakers of the past, with creations that look nothing like the signature “frog” watches such as HM No 3, nor like spacecraft propulsion units such as inspired HM No 4.

In under eight years, Büsser – a youthful 46 – has guided MB&F to a point where it just may be the most outrageous brand in the whole of haute horlogerie. When asked how he chose the individuals with whom he collaborates, this busy designer, entrepreneur and micro-engineering expert explained that it is undertaken on a project-by-project basis. But he remains in full control, a benevolent dictator.

“I learned one thing from my mentor, the late Günter Blümlein who was managing Jaeger-LeCoultre at the time I worked there, and who recreated A Lange & Söhne; I was lucky enough to work for him.

“One day, I was battling with him at a product meeting, because I was the only one who had the guts to battle with him. After five or ten minutes of us each defending his side, he looked at me and he said in his strong German accent, ‘Mr. Büsser, creativity is not a democratic process.’ And that is probably one of the two or three best lessons I ever got in my life. ”

Thus, MB&F is Büsser’s “baby”, a platform for his ideas, for his creative process. But to realise them, Büsser admits, “I have to find people who can translate my crazy ideas into reality. That’s where the process starts. I’m lucky enough, after 22 years in this industry, that I know a lot of great people.”

For the design itself, Büsser always works with Eric Giroud. “He’s one of the only people I know who can actually read my sketches and intentions, and transform them into 3D designs. From there we decide, which engineers, which watchmakers, are the most able to transform that design into reality.”

Initially, when he started MB&F, Büsser only worked with people he knew from past experience, artisans, engineers, watchmakers he’d worked with at Harry Winston or Jaeger-LeCoultre. Then, over the years, he says, “The friends of my friends become my friends, meaning, for example, that one supplier tells me, ‘Oh, you should try and work with this guy – he’s really amazing.’ So you meet him, you discuss things with him, got a good feeling with him, and you start working with him.”

Because the calibre of the outside partners is so high, they do contribute more to the projects than just the element for which they were selected. Büsser welcomes the input. “Some of these partners bring new ideas to the projects. Sometimes I have to say, ‘No, I don’t like it,’ and some are really great ideas. Soo from then onward, we will modify the concept because one or the other has had a great idea, and then it evolves.

“That’s how we work. It starts with our idea, which we then try to make a reality. Then it will be modified by engineering or some other ideas, and then on to the final product.”

Because MB&F is as much a “dream factory” as it is a watch manufacture, Büsser has expanded its scope beyond timepieces – but the values remain the same. The recently-launched Music Machine, with music box elements produced by Reuge, is a perfect example, a non-horological object that has become one of the most widely discussed of all MB&F’s creations.

Büsser, familiar with and deeply fond of Reuge’s music boxes, saw in them the potential to do something the respected Swiss manufacturer – soon to celebrate its 150th anniversary – might never have considered. It remains the world’s most revered maker of music boxes, but Büsser felt that, ‘It was a little bit irrelevant to who I am today. I adore their craftsmanship, I adore the idea, the people there are really amazing, but that was not the music box I wanted to have in my sitting room.

“I know it’s very self-centred, but at the end of the day, that’s what it is. So I showed them the design we’d done, and asked, would you agree to craft a music box like that? And they fell off their chairs initially. But they made the object virtually, exactly like I designed it – amazing.”

MB&F also produces or represents non-horological, outré creations under their M.A.D. Gallery banner, items as far removed from watches as “penny farthing” bicycles and guitars. This features in the world of MB&F to serve Büsser as what he calls his “playhouse.”

“It is everything I would love to own, but at the end of the day, there’s one central theme to everything that we present: ‘Mechanics can be art.’ M.A.D. stands for “Mechanical Art Devices,” so the creations have to be something mechanical, which has been created with artistry, so it can be something which is complete art, like the motorcycle by Chicara Nagata.”

Nagata has produced only five motorcycles in 15 years. Büsser speaks about Nagata with unmistakeable awe in his voice. “He spends 7000 hours on each piece, and never sold one in his life. He makes ends meet by doing graphic designs so he can eat and pay his rent. He doesn’t care about it. He told me, ‘My wife has left me, I have no more friends, but I can’t stop doing what I do.’ That’s incredibly powerful.

It goes back to the desire not just to work with people beyond the core personnel at MB&F, but to make available highly desirable objects beyond the core of MB&F per se, which is most assuredly wristwatches. “We only present the products of people we admire. It’s not about the product itself. It’s about the people behind it. By showcasing creativity in other domains – motorcycles, lamps, kinetic art – but following a similar life experience, and bringing us to where we are, it becomes something coherent.”

To which we, rather than Büsser himself, might add “audacious,” “entertaining” and, indeed, “mad.”

(Bespoke, 2013)