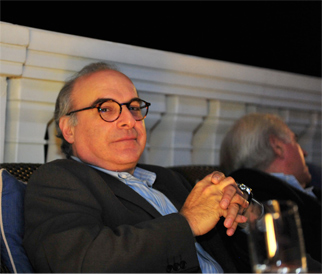

(Marcus Margulies, left, with Piaget’s Philippe Léopold-Metzger)

His grin falls somewhere in-between cheeky and amused when asked how he “got into watches.” Marcus Margulies has a two-word reply: “By birth.” No great secret there, though, for the watch-selling community, as Marcus was known to have inherited his father’s business.

“That was easy. My father came to England from Poland, he didn’t know a word of English. He came to sell clock movements for a friend of his, and moved into watches – and he became very successful. His dream was that I would follow him, and I never wanted to do anything else.

“I always really enjoyed it. I went to visit him when he worked, and it was always taken for granted, and frankly, there was nothing that I liked more. It was a no-brainer.”

A mere five minutes with Marcus re-affirms that. Although he swears blindly that the industry has changed not necessarily for the better, and the “r” word – “retirement” – crosses his lips occasionally because it comes with being a 60-something, the doyen of upscale watches in Bond Street is incapable of hiding his enthusiasm. A brand is mentioned – it doesn’t matter whether it’s one that he sells through his store, Marcus, or distributes via Time Products, or if it’s sourced from one of his rivals – and a learned, incisive discourse commences on the brand’s viability.

Among the many developments Marcus has embraced and promoted are grand complications including minute repeaters that chime the hours and minutes, perpetual calendars with date and moon-phase, and a personal favourite of his: tourbillons. In these watches, the heart of the movement rotates, the design originally conceived to counter the effects of gravity; in a wristwatch, it’s more of an intellectual challenge. Tourbillons are certainly difficult to manufacture and expensive as a result. Marcus stocks 40 or more.

While taste matters to Marcus as much as anything, he’s not averse to a bit of bling-bling. Among the treasures in his store are Franck Muller watches covered entirely in diamonds, along with Piagets, Vogards and others with one thing in common: none are ordinary.

When Marcus speaks, mere mortals listen: sales personnel, journalists, manufacturers. Over the years, Marcus and his companies have handled the crème de la crème of fine timepieces, both classic brands from the likes of Audemars-Piguet and Vacheron Constantin as well as post-1980 “new wave” arrivistes. His eponymous store is one of the most elegant (and well-stocked) on Bond Street, notorious for the upper levels with home theatre, gourmet dining facility and a fabulous wine cellar. Recent legislation, though, may put paid to enjoying the selection of fine cigars.

It’s not strictly cost-no-object selling. Marcus addresses the mass-market through his ownership of Sekonda – one of the largest entry-level watch producers in the world. It adds to Marcus’ credibility and respect, even from his fiercest competitors, but his legend is based on two primary qualities.

First and foremost, Marcus was among those who survived the terrible purge of the quality watch industry, when quartz arrived in the 1970s, decimating brands that couldn’t segue quickly enough from mechanical movements. When the backlash hit, and quartz was seen as the down-market, negative-equity ephemera that it is, Marcus and a handful of others were there to re-introduce mechanical movements to a new wave of discerning clientele. It coincided with revived popularity for fine cigars and wines, bespoke tailoring and luxury goods in general.

Secondly, Marcus’ combines years of experience with refined tastes, resulting in his habit of championing fascinating new brands. While he has trusted personnel who could do this for him, Marcus likes to trawl the annual Basel watch fair looking for exciting new watch houses; among the latest to earn his benediction are Vogard, Urwerk, Jorg Hysek’s H3 project and Greubel-Forsey. But nothing beats a lifetime in the business.

Marcus joined his father’s company after working in Swiss watch factories, his hands-on apprenticeship. “My idea after that was to travel to various places around the world, spend nine months looking at businesses and learning; this was after having been to Switzerland to learn the languages, and after doing very menial jobs in the factories themselves. But one of our managing directors left, so my father thought he should throw me in at the deep end. He probably also had an over-exaggerated idea of my ability.

“So he threw me in at the deep and … my only regret is that I wish I had travelled more, and had more of a youth. This happened when I was about 22. My father gave me the chairmanship in 1977, on his 75th birthday. We then had huge trouble in 1982 when our Hong Kong operation totally over-expanded, so major changes were made in the company and we took on a professional chairman.”

Marcus felt that this wasn’t merely sensible, but long overdue. “What happened was that we were running a public company as a family business, and since ’82 we ran it as a public company. And strangely enough, the disciplines that we had as a public company are still prevalent in the way we run the business.” The company returned to private status six years ago.

Marcus does not allow his passion for watches to overtake his need for a commercial, realistic or dispassionate eye. He does not consider himself a collector, despite his appreciation for “complications – the functions of expensive watches beyond mere time-keeping – and for hand-craftsmanship.

“I’ve got watches that I’ve acquired over the years, but I now want to change it around a bit, and change the focus of the watches that I wear. I guess when I was young, and more impressionable, I bought what I though were ‘pretty’ watches, pretty pieces at that time. What I prefer today are much more interesting pieces.”

In Marcus-speak, “interesting” generally means a product of an inventive mind, with a refreshing take on styling, a novel movement, exotic materials, or preferably a mix. During After Hours’ interview, Marcus was wearing one of his leisure-time favourites, having just come back from Italy: a Hublot “Big Bang”, one of the hottest watches around. Only his had an individualist’s twist: Marcus chose the version with white bezel and white rubber strap, the watch industry’s idea of “irony” in a timepiece to the north of £5000.

“I still think there’s got to be an aesthetic quality to them, but there’s so much more to a watch than just looking nice. It’s got to have a soul. You know, if you’ve got a dumb blonde, it’s not bad for the short term. But you want somebody with brains.”

Because he long ago stopped looking at watches as simply pieces of jewellery that tell the time, and because the high-end watch market has never enjoyed a more sophisticated customer base than it does today, there’s something of the evangelist about Marcus. And this touches on a slightly schizophrenic side to his business: Marcus rates Bond Street, and London itself, among the five or six most important “watch capitals” of the world – up there with New York and Geneva. Equally, he bemoans the fact that probably 70 percent of up-scale watch purchases go to foreigner customers, not the British.

“If you talk about the top level quality-wise, rather than price, I would say that there’s a singular lack of appreciation in England, compared to any other market. If people [in the UK] buy a Patek Philippe, they generally buy low-end models, because they think they should be wearing a Patek; the advertising works.

“High-end watches are tremendous today – there are a lot of very small watchmaking brands who are turning out amazing quality merchandise, but I would say that a lot of that we don’t sell to English people. That being said, we have a handful of very knowledgeable and highly passionate collectors.”

This surfeit of foreign customers is due in no small part to greater wealth abroad, especially the emerging millionaire and billionaire territories such as China, Russia and India, along with the traditionally wealthy clients from Japan, the Middle East and the USA. It is probably possible to track trends in wealth by studying the addresses of Marcus’ customer base. And Marcus has no intention of relying on bonus recipients in the City.

Succinctly, with resignation rather than contempt, Marcus deals with that potential market with what sounds like an ideal poster slogan: “City people are too busy working to spend their money.” Unlike thrusting City types, Marcus never lets work overtake life, and his world away from watches includes a passionate love of music, fine art, great wines and dining with “people I like.” But even then, watches are never far way.

Once started on the subject of the British consumer, Marcus regrets that the newly-wealthy still opt for what he calls “no-brainer” watches, obvious choices such as Rolex or Cartier which announce that one has “arrived.” And the spend is lower overall, Marcus reckoning that the average price of a UK watch is one of the lowest in Europe. Is it changing?

“Slowly. But the gap [between the UK and the Continent] will never narrow. The men buy a good watch which they believe will last for a lifetime; they have a great deal of pride wearing their father’s watch. The women are the poor relations. You go to a place like Glyndebourne, and you see the way the corporate wives are dressed – the French lady will spend more on a pair of shoes than the English corporate wife has on her whole body.

“For UK executives, the wristwatch does not have the status or the cachet that it has abroad. There are other values in England. It’s sort of chic to wear very old clothes. England is a society – forgetting about the City, the huge money, which is fairly recent – if you look at the English achievers, they’re mostly people working for public companies and they are very mundanely dressed.”

So, too, the outlets for watches. “In England, the main watch stores are all multiples. There are very, very, few really good, privately-owned individual outfits. In France and in Germany and in Italy, it’s all private, individual stores, and they’re dealing with private individuals. There is an absolutely different culture. There’s a culture of independence, of background and of knowledge.”

Despite the hard work of selling fine watches in the UK, compared to other markets, Marcus isn’t wholly pessimistic. “As people travel, and they’re exposed to more and more, their taste gets better.” And there’s a store on Bond Street waiting for them.

Marcus’ Words of Wisdom: How To Spot A Great Watch

“I would say that the way that you can see anything good in any field is to go to an expert, ask their opinion – an unbiased expert – listen, then make up your own mind. And follow your instincts.”

“It’s the same old story: you don’t go to a dentist and tell him how to take out your teeth. Or you sit down and really read about watches, and find out what’s best, and follow all sorts of auction results, etc, etc. You go ’round and you see what the major jewellers stock, what people wear.”

“[Brand X] places its watches on the wrist of Wayne Rooney. Now I wouldn’t have thought that he was an arbiter of taste for the sort of watch that someone who wants a great watch should buy.”

(After Hours, 2007)