In my other life – that of an audio reviewer – the atmosphere is one of such deep distrust that a writer so much as seen having a cup of coffee with a manufacturer is deemed to be on the take. While every industry has its differences, the independence of the writer is paramount regardless of the topic, especially of late when such scandals as the hacking of others’ phones have painted journalists to be as vile and corrupt as bankers, politicians or, yes, lawyers.

Some newspapers and magazines, such as American publications, are so draconian in their efforts to keep their journalists free from taint that – and I mean this literally – even the aforementioned cup of java is verboten. One can imagine how this hamstrings both writer and publication if it hampers the free flow of information.

Reality, though, demands a happy medium somewhere in-between the complete denial of any contact between a reviewer and a manufacturer, and outright backhanders, such as 18k rose gold tourbillons on the wrists of scribblers lucky to net £40k per annum. Which is why I prefer to wear vintage watches. Or carry the receipt for any new wristwatch I may own.

Still, a problem arises for those who believe in total isolation from the manufacturers because of the need for journalists to visit factories, watch fairs and other events, to gather the information for their readers to, er, read about. Yes, some magazines can afford to send their writers to events, picking up the tab from door to door, but most cannot. To put it another way, if car magazines had to buy the cars they review, in the interests of total independence, you’d never see coverage of anything above a Dacia.

Those who constantly accuse the press of being too easily influenced need to grow up. Merely attending a factory tour is no indicator of being “bought,” because upon his or her return, the watch writer can only report on what he or she saw. It’s the spin that makes the difference. But then, watches are unlike ALL other luxury items, whether it’s wine, or cars or hi-fi, or boats, or fine foods, because of one fact, which should be tattoo’d on every watch writer’s knuckles:

All Watches, From £2 To £2m, Have To Perform The Exact Same Function With Total Accuracy: Tell The Time.

There is no room for subjectivity in the ultimate verdict on a watch. It either tells the time correctly, or – in British legal jargon – it is of non-merchantable quality. In other words, it’s defective and cannot be sold legally in the UK.

After the accurate timekeeping has been established, though, everything else is subjective, from whether the writer prefers Breitling to Zenith to Omega, or rose gold over yellow, or 39mm cases over 44mm. And while the gift of a watch may influence that bias, the fact remains that all watches have to tell the time in the same manner, and everything else is a matter of taste.

Unfortunately, the most important practical aspect of a watch’s quality – that of reliability – is something that can only be assessed with the passage of months or years, clearly not possible unless you want the review of a new watch to appear around the time its replacement is launched.

But back to journalists’ behaviour, with a perfect example of etiquette. If you go to Japan or the Middle East on business, you will receive a gift. While a reviewer can act holier-than-thou at Baselworld or SIHH, and eschew the goodie bags, to decline a gift in Japan or the Middle East is to insult the host.

This is a genuine and serious cultural difference, but the gift of a bottle of sake, or a pair of headphones, is hardly the same as some guy named Vinnie slipping you an envelope full of used twenties. Or some sly PR person strapping a minute repeater on your wrist from his or her “war chest,” as one London PR called his stash of freebies.

Even the most puritan of critics of press ethics will admit that there’s a quantitative difference between writers being “gifted” a scarf or an iPhone case and a £100,000 Grande Complication. For some, though, even a £2.95 Starbucks espresso is beyond the pale.

While it is easy for writers to dismiss most complaints as mere envy – and who wouldn’t want to review cars for a national magazine at the highest level, testing Porsches and Aston Martins and Ferraris, or enjoy the perks of being a food critic, or theatre critic, or travel writer? – it’s human nature for the readers (especially in Great Britain) to assume that all writers are bent.

Two disconnected incidents brought this situation to mind, the first being the perennial complaint from a hi-fi magazine reader who wondered how audio writers managed to acquire hugely expensive systems. The second came from a watch industry colleague.

This is not the place to bore you with hi-fi politics. Hi-fi differs from ALL other pursuits in that the reviewers have to own decent systems in order to review other hardware. For example, you cannot review speakers on their own: you need the rest of the system. Watches, cars, cameras and so on are standalone items. A critic needs nothing beyond the experience and the skill to assess them.

Anyway, as regular as clockwork, a disgruntled reader will demand full disclosure of how audio reviewers acquired their systems. I own half of my equipment and borrow the rest. Note the lack of quotation marks around the word borrow: these are products I must have in order to work, but which I cannot afford, so mine are on loan, and not “permanent loan,” I hasten to add. Furthermore, it stands to reason that reviewers would only borrow equipment that they rate highly. Why would they borrow junk?

But with watches, there’s no need whatsoever to “borrow” an 18k rose gold tourbillon. Wearing it will not make the writer understand its workings any more than the press release that preceded it. If a writer doesn’t already know what a 60-hour power reserve is, or how to set the triple calendar, then that hack shouldn’t be writing about watches, let alone wearing them. As for the brand representative who gifted such a watch, they’re merely doing their job by rendering a journalist “malleable.”

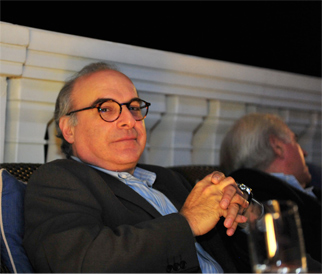

Which brings me to the second incident that brought this topic to mind. A respected colleague phoned me to discuss a seminar about vintage watches. His opener was that I was one of the few he knew who actually bought his own watches.

Not that this is any guarantee that a writer is to be considered eminently trustworthy just because he or she paid for his watches, as some do. Even total disclosure or transparency may not be enough to dispel suspicion. I once loaned a watch to a fellow scribe who was instantly greeted with, “Who did you suck up to for that?” – a pretty rich challenge since it came from someone overly generous with free watches. That person’s face dropped when my friend said it belonged to me – and that it was 12 years old. But no apology followed.

Years later, when the same writer bought a currently hot watch, a similar slur occurred. She’s probably taken to carrying around the receipt, just to deflect such accusations.

Is there a point to all this? Probably not: the watch industry, being an extension of the fashion industry, is fuelled by goodie bags and trips and lunches. As are too many others to list. If you have a conscience, or wish to exhibit some semblance of integrity, you simply get on with your work.

Me? I just delight in wearing watches older than most of the journalists in the watch biz. How they got theirs is, ultimately, their own business.